Throughout the three years of the pandemic, there has been a noticeable emergence of new collectors from China, as evident on social media platforms such as Little Red Book (often referred to as the “Chinese Instagram”). These collectors share their new art purchases through unboxing videos and promote artists they admire. However, due to travel restrictions, many have been unable to attend international art fairs.

With this in mind, I delve into many questions on this subject: How can we consider differences in tastes and preferences between Chinese and Western collectors? What sources of information do Chinese collectors rely on to stay informed about the art world? How do Chinese collectors stay informed about the latest trends and developments in the art world? What impact does social media, particularly Little Red Book, have on the art collecting habits of Chinese collectors? How have travel restrictions during the pandemic affected Chinese collectors’ ability to engage with the global art market?

Simon de Pury mentioned that the new collectors from China he had encountered during Art Basel Hong Kong, have both “youth” and “energy”. Indeed, the overall impression I got from the attendees and clientele I saw at the fair on VIP day, after not having been back to China for three years, was the same: a cool crowd of mostly young, trendy men and women, a lot of them wearing streetwear.

Simon de Pury added, “One dealer from London told me that when he goes to art fairs in Europe, people ask him about his summer plans. But he’s not interested in discussing these, only in attending art fairs.” He said that in HK, everyone was engaging with the substance of what was being exhibited. They want to learn more and know more; it’s that curiosity and the dialogue that make it worthwhile and exciting. Indeed, Chinese do not like wasting time on small talk (unlike Europeans who Simon admitted have a tendency to do so), rather preferring to focus on acquiring new knowledge. This is a country where everyone is encouraged to work as much as possible to reach their full potential, and taking it at a slower pace to enjoy the ‘joie de vie’ is rare.

Europeans actually see a lot of art when they “waste time” on holiday – combining art with leisure and down-time is nothing new. This is also integrated in China, but here art is used to boost commerce and attract more instagramable and young audiences.

Often those ‘in the know’ of the artworld are prone to scorn artworks in hotel lobbies, considering them to be too ‘decorative’. However, when I spoke to Nai Qian, the 25 years old owner of Keyi Gallery in China’s second tier city Hefei, whom I met in Singapore, he told me that there was in fact a real need for ‘lobby art’ in China, otherwise many young people were only seeing and learning about art through auctions.

As to whether new collectors in China pay attention to emerging artists who have not yet been promoted by the mainstream market, Nai Qian said something that struck me: “In China, seasoned collectors are more excited about collecting young artists and discovering young talents, while young collectors are excited about buying ‘hot and trendy’ artists who are already validated by the market”. This is common in China, public institutions are considered weak and there is a lack of state-run museums. Additionally, a lot of ‘institutions’ are funded by corporate or private bodies, meaning a lot of corporate-funded institutions are more concerned about their ‘box office’, thus, the content they selected tends to be more attractive to the public and less academic.

Despite his young age, Nai Qian is not new to collecting, before founding his gallery, Nai Qian started sharing artists he liked on WeChat subscription account; and it was through one such post that he acquired his first collector.

Social media is a strong factor influencing the taste and interests of aspiring collectors. It’s not difficult to realise this once you consider how much effort auction houses put into developing their RED and WeChat. Such places will pay influencers to develop wider audiences outside of the traditional art collecting crowd and encourage their employees to set up their own personal accounts and develop their personal brands to drive more audience to the auction houses. As a result, more new collectors learn about the art world and market through these auction houses instead of museums and institutional shows.

Nai Qian said that the two works he bought this time were from Melike Kara by Jan Kaps and Santiago de Paoli by Jocelyn Wolff, both artists he has been following for a long time. It is instances such as this that are a testament to the power of social media in China’ careers, influence and power can be made and grown through likes and shares.

Left: Santiago de Paoli, City Moons, 2018, Jocelyn Wolff

Right: Melike Kara, Khailani Tribe, 2023, Jan Kaps

In fact, not only do art industry people come to Hong Kong to gain new inspiration, they also meet new collectors. Nai Qian, the owner of Keyi Gallery, told me that originally his gallery had very few local collectors, mostly ‘old’ collectors from major cities like Shanghai and Beijing, and after all, in China’s new first and second tier cities, it is not easy to develop local clientele because of the lack of a well-developed art ecosystem and the high cost of education, but this time when he flew in from Hefei, he heard the staff at the check-in desk say, “Why are so many people going to Art Basel Hong Kong this time?”. It seems that if Chinese and foreign art industry people want to tap into new collectors in China, Hong Kong is still the best place.

I also talked to some collectors who have been actively travelling to international art fairs as well as some mainland China-based young collectors during my recent trip. I found that over the past three years, the mainland so-called “PDF collectors” have diversified their tastes. The information gap does still exist; some artists who already have a “waiting list” in Europe or the US are still quite fresh and new to the Chinese audience; some artists that European collectors are already tired of seeing, are still new to the Asian market. Although some people commented that there was nothing new at Art Basel in Hong Kong, I felt that there were many more new artists to discover than at Frieze in London last year and also so many Asian galleries present.

Some European galleries who have a good reputation for their taste in programs and are recognised in the circle had unexpectedly low numbers at their booths at Art Basel in Hong Kong. I found that Europeans don’t consider how well a particular gallery sells when it’s a good presentation, but rather prefer to discuss the taste of the gallery’s programmes, or even praise them for not following the mainstream trends keeping it niche in the market. Whereas people in mainland China are always more concerned about how well a particular gallery sells and also how well it does business. A young domestic collector, who asked to remain anonymous, on her first time abroad in three years told me that she found European gallery sales to be more patient than those in China, and that even if a customer did not show intention to buy, the sales would cater to them patiently.

Those international jet-setters, who have not missed a single exhibition worldwide in the past two years, find it more interesting to visit new places with ‘local’ art projects or artists they have not heard of before. Alan Lo reveals that his foundation, coincidentally, found the same selection as Filipino collector Tim Tan, and that Empty Gallery’s booth and satellite programme this year have been well received and have received a nod from Jeffrey Deitch as well.

In Tim Tan’s selection of images from the exhibition, there is a work by Maria Kulikovska of Double Q Gallery, which is also the favourite of Monique Leong, a young collector from Macau who now lives in London. Monique told me an anecdote about how she stopped her mother, who is also a collector, from “spending on impulse”: her mother saw a work by the artist Stephen Thorpe at the Ora Ora stand, which was a new discovery for her at the fair, but Monique had seen a better work by the same artist at last year’s NADA show, which prevented her mother from impulsively acquiring the painting. Monique also liked the work of Double Q Gallery artist Artem Volokitin at this year’s ABHK and the work of Cary Kwok presented at the ABHK stand at Herald St., London.

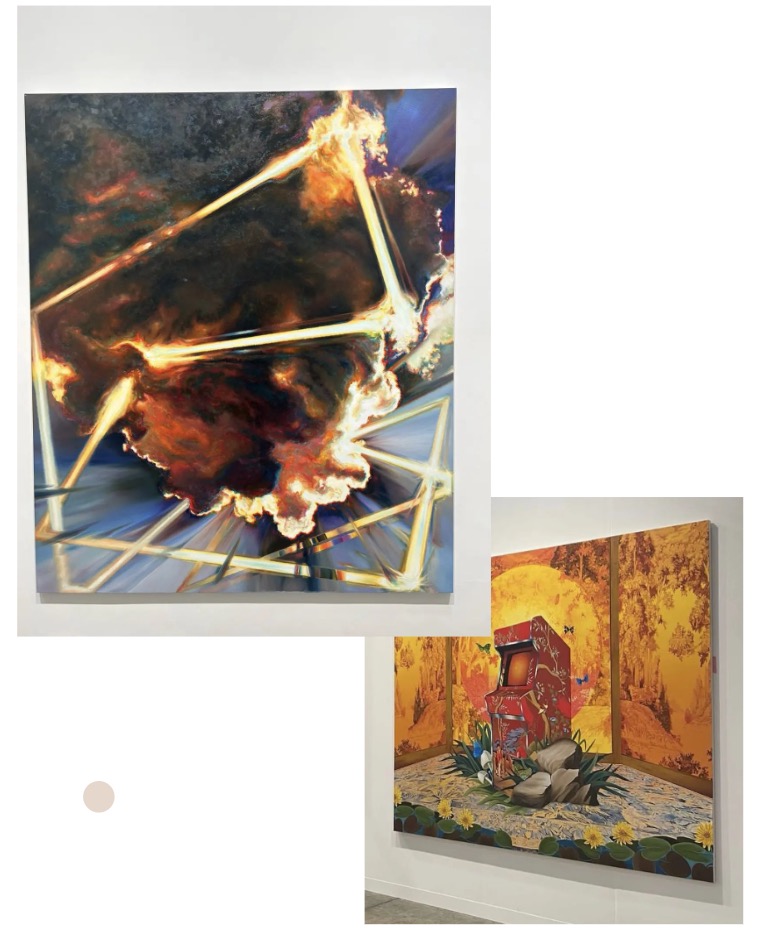

Top right: Cary Kwok, Herald St.

Bottom left: Artem Volokitin, Double Q

Bottom right: Stephen Thorpe, Ora Ora

It is very important to be able to travel a long way and see the works in person. For many domestic ‘PDF’ collectors who have not been abroad for three years, the possibility of this ‘face-to-face’ experience with a work by an artist they have long been fond of is also quite interesting. That said, some were disappointed with the actual Flora Yukhnovich works brought by Victoria Miro, perhaps because they had not seen the better quality works that had fetched so much at Sotheby’s London.

In a previous article analysing the phenomenon of the parallels between the art market and contemporary dating culture, I wrote that buying a painting online via PDF requires somewhat similar levels of seriousness to consider the profile of a potential online date. If the price is low and cheap, it’s an easy decision, but if it is so expensive that you have to spend a thousand dollars, perhaps “online dating” will never work for you. Rather, you would need to get a feel of the temperament, aura and attraction face to face!

This is the style of Niklas Chou, a friend of Nai Qian’s and a new collector from Generation Z. He was a ‘PDF collector’ for two years after the pandemic began and while still at university, set up the art space ‘69 Art Campus’ in his home office in Beijing. Before that he studied in Germany and spent a lot of time collecting beforehand. Following his studies, he spent time in Basel, Switzerland, before he started collecting, and saw many companies present their ideas for collecting through group exhibitions. Niklas is still studying at university, and recently I have been encountering a lot of young first generation collectors, who are still students, some of them even become dealers too. These are the second generation riches, who can sell directly to their friends circle and have become a common phenomena in China.

Many of the young Chinese collectors I met in Hong Kong were art industry people, indicative of the current trend of second-generational wealth working in this field. I spoke to a local collector, Chuan, a Malaysian Chinese who has lived with his partner (also in the arts) in London and Hong Kong for many years, about the advantages and disadvantages of working in the arts and being a collector. Due to travel restrictions during the pandemic, many new collectors’ access to information was through Instagram and Little Red Book, but if they wanted to learn about new artists through social media, they would inevitably be influenced by the algorithm. Instagram uses an algorithm to place works that users are likely to prefer and interact with at the top of their feed, in this sense, your interaction with art is limited to your algorithmic preference and limits your chances of discovering something new.

When an artwork has been purchased online, the moment of unboxing becomes incredibly exciting, as Chuan described, “because you don’t know whether you will get a ‘surprise’ or a ‘shock’ when you open it!”. Interestingly, artwork unboxing videos are currently trending on Chinese Instagram – Red. In China, people like to show their purchases, encouraging consumerism, but also triggering interest from aspiring collectors. Collectors tend to create and build their personal brand on this platform, showing videos of their latest buys or making educational content to demonstrate their knowledge of the art world. Likewise, in the west, many collectors share aspects of their day-to-day lives, but for young Chinese collectors, this is a serious matter; they put effort into their content and often have a team to manage their social media and build their IP.

As an art industry worker, Chuan’s partner believes being a collector is not always easy, as many galleries hold you to a ‘stereotype’ of those who work in the industry and protectively assume you may be a dealer or flipper. Many art advisers are also ‘discriminated against’ when they buy for themselves and at some galleries encounter prejudices, as Chuan told me, “artists are specific about not selling their work to art advisers.”

In addition, although it is not always reflected in the Hong Kong Art Basel scene, buying in Europe is actually very difficult, and galleries prefer American and European institutions and clients when placing works, especially as many conservative galleries are now specifically targeting Chinese people, fearing that the work will be flown off immediately. One collector I met in London told me that she now has to buy works in her foreign husband’s name. It is likely that as the demand from Chinese collectors grows, and the “discrimination” towards Chinese collectors increases, this will lead to a number of ‘cross-border marriages’ being formed for the purpose of buying works.

The market is ever-growing in China, especially due to the increasing amount of curious and tech-savvy young collectors. Other identifiable groups include globe-trotters, top collectors, who stay ahead of the game by keeping incredibly well informed of the market and its trends; PDF collectors, who garner most of their knowledge from social media and domestic shows. But, there’s an information gap between these groups and the West.

While there are some well-known western galleries in China, if they fail to have a Chinese representative, even industry people won’t have heard of them. The question remains, if the galleries and Western businesses are interested in tapping into the new market, they will need to adapt to Chinese ways, not staying speculative and sticking to traditional Western ways. Otherwise, these new, wealthy groups of collectors, such as the avid PDF types, will be unattainable to them, and they will remain limited to the small, niche group of international collectors who are old-time players of the art game.

Text: Luning

Copyediting: Rosie